A few days ago I wrote a post entitled Quantify Yourself. The premise was simply that you have to know your own personal sales metrics, and that it is your responsibility to both know your metrics and to improve them. I linked to this post in the News section of the Modern Selling group on LinkedIn, and a couple members of the group made some valuable comments. I asked Alan Timothy of i-snapshot.com to post his comments here, so that I could share his valuable perspective and so that I could add my thoughts to his comments.

Less is Not More

Alan suggests that my original post misjudges the “relative importance between the ‘numbers’ and the ‘magic’ and is not based on fact.” His interpretation of my post is that it “read a bit like the other Sales myth that the less I do the better I will be.”

Alan’s comments sent me rushing back to my post to make sure I didn’t use the word “magic” (I didn’t), and that I didn’t write anything that would suggest that less is more (I didn’t). What I did suggest, and what I will vigorously defend is the following:

- Less is not more, but more is not always more either

- “Better” is always more, but “better” is a more difficult result to achieve. Therefore, we mistakenly work only on activity.

Less Is Not More. More is Not Always More.

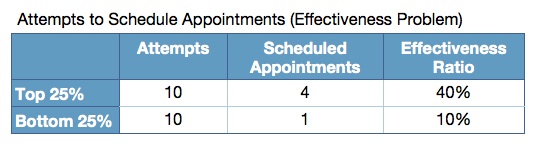

I have never suggested that a salesperson could improve their results by doing less of anything, other than eliminating the low impact, low priority activities that rob them of their time and their results. Let’s take a look at a real life example of what I am suggesting about effectiveness. The following chart shows two groups of sales people. The top 25% are able to schedule appointments with 40% of the qualified prospects they attempt to schedule. The bottom 25% of sales reps is able to schedule with only 10% of the qualified prospects they attempt schedule.

It is possible to double the number of scheduled appointments of the bottom 25% by insisting that they double their attempts. It is also possible to double their scheduled appointments by improving their effectiveness. The question is: Which option do we in sales and sales management choose and why?

There is an old saw about sales managers having a “More” button on their desk but not having an accompanying “Better” button. Requiring salespeople to make more attempts is easy to require, but much harder to convert to results. It is too easy to pound on the “More” button without generating the expected increase in results. Simply requiring more calls usually results in more appointments with unqualified prospects and greater sales expenses without any return on the investment. (For more on this see Modern Selling publisher Neil Warren’s response to both my post and Alan’s comments on the Modern Selling group here.)

The bottom 25% lack the skills to be as effective as we might need them to be. Requiring them to double their output leads to frustration, burn out, complaints about prospects, and a whole range of excuse-making behaviors that does little to improve their results. The correct approach is to improve effectiveness when effectiveness is the problem. Which bring us to activity problems.

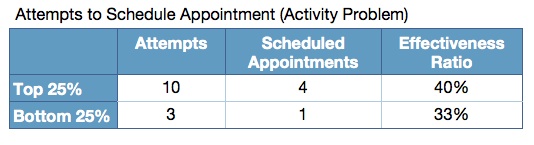

When More is More

More isn’t always more. But “more” is the answer when the problem is a simple activity problem. This illustration is where requiring more calls is the right solution. In this example, the sales reps are effective, but they are simply not doing enough of the activity to generate results.

Alan points out in his comments that “the one thing which is the most highly correlated to revenue growth is activity. With the top quartile of a sales team typically doing twice the activity of the bottom quartile, then improving the bottom quartile has significant impact on revenues. It also turns out that those with higher activity rates also have the highest ratio of positive outcomes.”

I don’t have access to Alan’s massive database of 4 million sales calls by 3,000 sales reps, but I believe his data. The question, however, isn’t whether Alan’s data are correct; I believe it is spot on. The question is: What do you do now that you know this? If it is simply the fact that the higher achievers are more active, and if activity correlates highly with positive outcomes, then I should be able to choose at random ten salespeople off the street, require the same activity as the top quartile and massively improve my sales organization by generating the same results (and I don’t believe that this is what Alan is recommending). This ignores the effectiveness component completely.

Increased activity is the right answer when an organization is selling something that has a relatively low cost, a relatively low risk, and with relatively low complexity. This is often not the case in business-to-business sales, which now requires, among other attributes, a very high level of business acumen.

Most sales managers choose more activity because it is far easier than improving effectiveness. Period. But to do so is wrong, because it treats all problems as activity problems and disregards effectiveness problems. In business-to-business sales, activity problems are often really effectiveness problems; low activity is the presenting symptom.

Better Is Always More

When you improve a salesperson’s effectiveness, you improve their confidence that they can achieve the outcomes of the activities they are taking. When their confidence is improved there is less reluctance to engage in activity, which almost always results in improved activity and improved results (this is setting aside some percentage of all salespeople who easily fall victim to the Weapons of Mass Distraction: the Internet and email).

This post, like my original Quantify Yourself post, isn’t about sales managers. This post is about your responsibility for producing results. You may be required to double your activity to improve your results. You may need to improve your effectiveness to improve your results. You may need to improve both; I don’t know. What I am certain of, however, is the fact that it is your responsibility to recognize where you need to improve and that it is your responsibility to take the actions necessary to make the improvements. Better is always more.

The point I am trying to forcefully make is that activity by itself is not, cannot be, and should not be the end of our focus in sales improvement. I will even more forcefully make the point that is the salesperson’s responsibility to be actively and passionately engaged in their own improvement.

Alan closes his comments with this: “The magic can improve results but only once you have the numbers measured and managed.” I agree. Measure the numbers, work the magic of managing your own improvement.

.jpg?width=768&height=994&name=salescall-planner-ebook-v3-1-cover%20(1).jpg)